Climate Change Denial for Creationist Kids

Originally posted in Righting America, October 29, 2024, and reprinted with permission. Glenn Branch is deputy director of the National Center for Science Education, a nonprofit organization that defends the integrity of American science education against ideological interference. He is the author of numerous articles on evolution education and climate education, and obstacles to them, in such publications as Scientific American, American Educator, The American Biology Teacher, and the Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, and the co-editor, with Eugenie C. Scott, of Not in Our Classrooms: Why Intelligent Design is Wrong for Our Schools (2006). He received the Evolution Education Award for 2020 from the National Association of Biology Teachers.

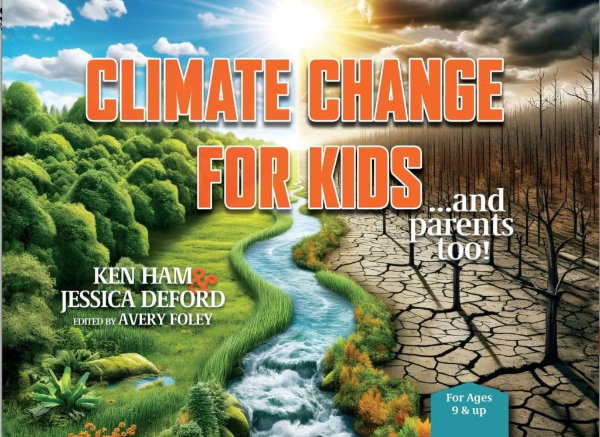

Climate Change for Kids…and Parents Too!, the latest entry in a spate of climate change denial books aimed at a young audience, invites the reader to “[d]elve into the science of climate change and discover how science, removed from assumption and speculation, reflects the history and truth found in God’s Word” (in the words of the back cover). The reference to God’s Word is distinctive: the propaganda efforts in the same vein from the CO2 Coalition, Mike Huckabee’s EverBright Kids, and PragerU are ostensibly secular. But the authors of Climate Change for Kids are Ken Ham, the founder of the young-earth creationist ministry Answers in Genesis, and Jessica DeFord, who, armed with a master of science degree in wildlife ecology, works for the same organization. In consequence, their book is a mix of error and fantasy, with the errors resembling those of secular climate change deniers and the fantasies emanating from their own reading of — and creative additions to — the Bible.

A fair amount of the eighty-page book purports to address the evidence for climate change and for anthropogenic climate change from the historical record. It would be tedious to describe all of its errors, but a central misunderstanding deserves attention. Acknowledging that “[t]he observational data shows [sic] that the global surface temperature of the earth has been warming over the past 100 years or so since it has been recorded” and reporting that the amount of warming is estimated to be about 1.5–1.8 °C, Ham and DeFord then caution, “But this warming estimate didn’t come solely from the observational data collected at weather stations and by satellites. It’s based on computer models. What you input into these models will decide what predications [sic] the computer model provides” (p. 18). A footnote offers a 2022 paper by meteorologist Roy W. Spencer and climatologist John R. Christy, both at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, as evidence for the middle sentence.

So what’s the problem? Well, the cited paper, “Dependence of Climate Sensitivity Estimates on Internal Climate Variability During 1880–2020 ,” is prominently labeled “This is a preprint; it has not been peer reviewed by a journal.” So Ham and DeFord have no business citing it. A version of the paper was later published in the journal Theoretical and Applied Climatology, although it seems not to have attracted significant scientific attention. More importantly, though, in neither version of their paper do Spencer and Christy claim that the warming estimate is based on computer models. And that is simply because the warming estimate is not based on predictive computer models! Rather, it is based on observational data, namely, measurements taken by surface and satellite thermometers. True, both data sets require adjustment and correction in light of factors that introduce biases. But their close agreement, unmentioned by Ham and DeFord, is strong confirmation that the climate is warming.

Ham and DeFord conclude, “So the predictions don’t necessarily reflect the real-world, observational data” (p. 18) — which is odd, since no predictions are under discussion. They add, “And one study that compared computer climate models to the observational data found every single climate model they studied overpredicted warming,” citing a 2020 paper by Ross McKitrick, a professor of economics at the University of Guelph, and Christy. But the paper focuses on the ability of a certain class of models, not all models, to predict tropospheric, not surface, temperatures. (It is a robust scientific finding that we live on the surface of the planet.) A comprehensive analysis of climate models published between 1970 and 2007 found them to be “skillful in predicting subsequent GMST [global mean surface temperature] changes, with most models examined showing warming consistent with observations, particularly when mismatches between model-projected and observationally estimated forcings were taken into account.”

Illustrated here is Ham and DeFord’s general approach to handling the scientific literature on climate change: cite a single source that seems to offer evidence for the necessary point without worrying about whether it is legitimate, relevant, or confirmed by the bulk of scientific research. Sometimes, however, they abandon the approach in favor of bald assertion. Continuing, Ham and DeFord assert, with dubious coherence, “Climate researchers generally assume Earth maintains a constant average temperature and that our atmosphere traps more heat from the sun than what is returned to outer space” (p. 19), but they provide no examples of any researcher making such assumptions. Similarly, they claim that there is evidence that both of these “assumptions” are wrong, thus invalidating any models incorporating them, but they provide no references to such evidence. In any case, the views of climate scientists on these questions are not a matter of assumption but of evidence.

Despite their view that there’s no telling how much Earth has warmed since the 1880s, Ham and DeFord are apparently willing to concede that recent global warming is real. But they misrepresent the argument for its anthropogenic nature, writing, “Since humans burn fossil fuels and burning fossil fuels produces CO2 and CO2 traps heat … we must be responsible for any warming … right?” (p. 20, ellipses in original). In fact, climate scientists have not jumped to their conclusion as Climate Change for Kids suggests; rather, they have meticulously examined all of the known mechanisms capable of changing the climate and have concluded that greenhouse gases released by human activities are responsible for recent global warming. Popular explanations of the way in which they reached their conclusion are easy to find. For Ham and DeFord to misrepresent the argument so badly suggests at best that they are incompetent to write a book about climate science.

Paleoclimatology is dismissed on the grounds of a general skepticism about scientific knowledge of the past: “You can’t directly test, observe, or repeat the past!” (p. 33). “Scientists cannot 100% accurately describe past events if they were not there to directly observe them,” Ham and DeFord assert (p. 33), ignoring the fact that, far from claiming 100% accuracy, scientists typically report their findings with error bars. From a secular point of view, their emphasis on dismissing paleoclimatology is odd: until recently, paleoclimatological data (as well as historical data) were not considered to be as reliable as data from climate models, so the best evidence for the anthropogenic nature of climate change was from climate models — which are, of course, rooted in basic physics as applied to observational data. But Answers in Genesis, as a young-earth creationist ministry, is heavily invested in disputing the possibility of scientific knowledge of the past, and Ham and DeFord evidently want to put the investment to work here.

Thus Climate Change for Kids insists, “God and His Word is the ultimate authority by which we must discern all climate and weather information” (p. 53), and Ham — who nominally takes over the narration from p. 54 onward — explains, “As I’ve read the Bible to understand ‘climate change’ events that affect us to this day, God has revealed 7 climate ages divided into the history in the Bible” (p. 58). There are seven of these ages, presumably to rhyme with the seven days of creation; Answers in Genesis similarly discerns seven eras of history: Creation, Corruption, Catastrophe, Confusion, Christ, Cross, and Consummation. The alliterative muse apparently having deserted him, and no explicit nomenclature to be found in the Bible, Ham calls the seven climate ages Perfect, Groaning (i.e., postlapsarian, the label referring to Romans 8:22: “For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now” [ESV]), Flooding, Icy, Shifting, Fiery, and Heavenly.

Like the displays at Answers in Genesis’s attractions, the Creation Museum and Ark Encounter, the discussion of the seven climate ages (sprawled from p. 60 to p. 77) presents a reading of the Bible that both confabulates details that aren’t visible in the text (starting with the seven climate ages themselves) and fails to acknowledge a diversity of opinion among Bible-believing Christians. (On the attractions, see, for example, Susan L. Trollinger and William Vance Trollinger Jr.’s Righting America at the Creation Museum and James S. Bielo’s Ark Encounter; for organizations of evangelical Christians who accept climate change, see, for example, Young Evangelicals for Climate Action and the Evangelical Environmental Network.) Puzzlingly, the Groaning climate age is described as “continuing to this day, because God has not yet made a new heavens and earth to restore perfection” (p. 65); what’s the point of distinguishing among seven climate ages if there’s going to be overlap among them?

Climate Change for Kids is purportedly aimed at readers nine years and older, and there are features, beyond the color illustrations on every page, clearly aimed at a young audience, such as boxes headed “Let’s ask” and “Why then?” and “From God’s Word” (with highlighted and annotated verses from the Bible). Still, having a four-page introduction from a septuagenarian Australian complaining about the secularism infecting his college education in the early 1970s seems like not the best way to attract the intended readership. Similarly, a fourth-grader might gaze upon the admonition “When climate change panic is induced and alarms are sounded in the media or in the halls of academia, we must exercise discernment” (p. 11) with a degree of puzzlement. Many of the cited sources (with details crammed, in tiny text, on p. 80) would certainly be beyond the ability of a young audience even to comprehend, let alone assess for scientific credibility. (A number of those works are in fact not scientifically credible.)

But probably none of its readers are going to exercise discernment while poring over the arguments of the book. A five-star review posted at its publisher’s website comments, “I have it sitting on our coffee table in the living room (strategically placed!) and the kids have all flipped through it and learned so much!” “Flipped through” rings true. Rather, Climate Change for Kids is geared for a readership that expects Answers in Genesis to have answers — so to speak — to all questions of importance to the Bible-believing Christian and so is less concerned about the quality than about the existence of the answers. Owning a copy of the book, and thus manifesting solidarity with Answers in Genesis, is what matters. Unfortunately, the same attitude is likely to bolster continuing efforts to derail, delay, and degrade action on the very real disruptions caused by anthropogenic global warming that are already afflicting people, including Ken Ham’s base, around the world.

Acknowledgments. Thanks to Paul Braterman for useful discussion and to Barry Bickmore, Andrew Dessler, and Spencer Weart for discussion of the climate change literature.